“It is here that nobility resides,

where there is feasting and where comforts are nurtured:

a fair lordship and dukedom has been established near Basaleg.”

So wrote Dafydd ap Gwilym, in the judgement of many Wales’ pre-eminent poet in the 14th century, of Gwernyclepa, the llys (or ‘court’) of Ifor ap Llewelyn – known better by history as Ifor Hael (Ifor the Generous).

Ifor ap Llewelyn, second son of Llewelyn ap Ifor and Angharad of Tredegar, was assured by his bard, Dafydd ap Gwilym, that: “As long as the Welsh language continues your praise will be sung”. The name of Ifor Hael (Ifor the Generous, as Dafydd termed him) has indeed lived on.

Both Ifor and Dafydd had their family roots – it’s suggested that they were related – in Dyfed. There has been speculation that political problems involving Dafydd’s family forced the bard to move to Gwent. By any account Dafydd was certainly the most renowned bard of medieval Wales. It was at Gwernyclepa, at the court of Ifor Hael, that he enjoyed the munificent hospitality that inspired some of his greatest work. It was to prove an excellent partnership. Ifor could not have wished for a better man to sing his praises and, ultimately, to immortalise him.

This surviving twelfth century building at Boothby Pagnell, near Grantham, Lincolnshire, with its dramatic first floor entrance way and a fireplace with a hooded chimney built into the wall, may well follow a similar design to the long-dismantled Great Hall at Gwernyclepa, where Ifor entertained on a grand scale.

The atmosphere at Gwernyclepa in those days can be imagined – and the location for the heart of the entertainment would have been the Great Hall. Gwernyclepa was described as a centre of civilised living, as being the very symbol of gentility, grace and luxury, where the spirit of chivalry mixed with the ancient Welsh traditions. As head of the llys, Ifor Hael, Dafydd tells us (as he should – that was his job), was the embodiment of courage, wisdom, generosity and justice. He was compared to Rhydderch Hael, one of the three generous men of the Isle of Britain. The bard certainly enjoyed his stays: “Drinking with Ifor, and shooting straight-running great stags. And casting hawks to the sky and wind, and beautiful verses, and solace in Basaleg”.

Sadly for this idyllic picture, it was not just the free-flowing drink, and the great stags, and the hawking, and the singing, that appealed to Dafydd. Besides his obligations at the court bard, Dafydd was appointed to act as tutor to Ifor’s daughter. (You know what happened next, don’t you.) It can be imagined how the music and gaiety suddenly stopped when Ifor Hael discovered the daliance. Greatly disapproving of such a match, Ifor sent his daughter to Anglesey, an island in far-distant north Wales, away from the romantic attentions of the silken-tongued bard. However, Dafydd promptly followed to Anglesey, although his objective was ultimately frustrated, principally by the fact that Ifor’s daughter became a nun. The breach between patron and bard was not irreparable however (they needed each other in equal amounts), and Dafydd returned to Gwent, and resumed showering praise on Ifor. (In later years Dafydd again fell in love, again controversially, but this time – with his daughter safe in the hands of the Lord a couple of hundred miles away – Ifor welcomed Dafydd and his new love to Gwernyclepa.)

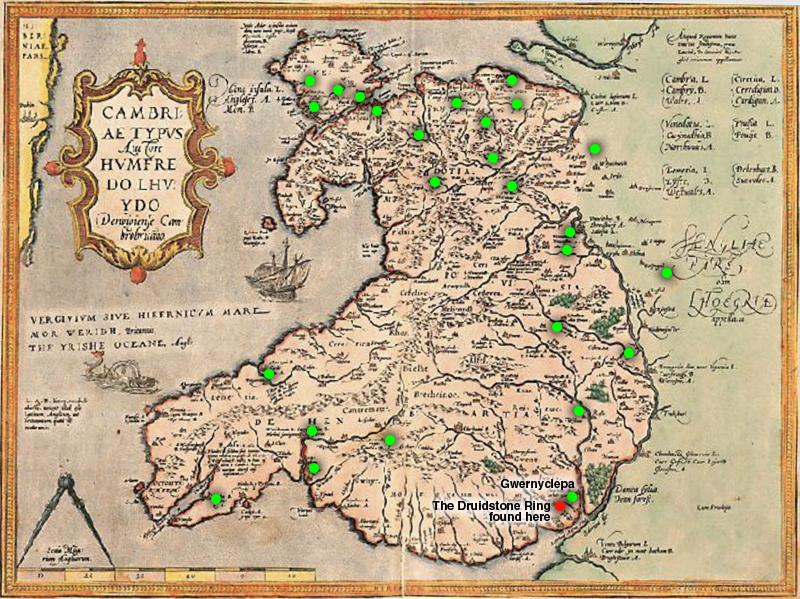

At this point you may be wondering why, of all the great houses in Wales, are we on focussed on Gwernyclepa. The map of Wales alongside goes a long way to explaining the reason. There are innumerable maps of Wales all over the internet; because geographical accuracy wasn’t critical to make our point we thought we’d use this one, from the sixteenth century. Looking at the map it’s obvious that Anglesey, the Llyn Peninsula and Pembrokeshire were at that stage relatively unexplored but it’s perfectly adequate for our needs.

The green dots on the map represent the locations of llys, or courts, which historical evidence has confirmed actively supported the bardic tradition. Immediately apparent is that the northern half of the country has the predominence of such locations. In the south there are five to the west and two to the east – of which just one lies in the south-east: this is Gwernyclepa.

Immediately adjacent to Gwernyclepa you’ll see a red dot; this dot shows where The Druidstone Ring was discovered. The distance between the two dots is 3 miles – that’s about 10 minutes at a trot, five minutes at a canter (no cars in those days). And where The Druidstone Ring was found is on what would have been the most direct route between Gwernyclepa and another nearby large country house – Druidstone House. Circumstantially, there are strong reasons to link Gwernyclepa and The Druidstone Ring.