So how many people with the initials ‘PW’, with a relevance to south-east Wales around the fifteenth/sixteenth century, could there be? Well, to date we’ve found nine candidates. Here, in approximate alphabetical order with the level of detail on each individual determined by the amount of research we’ve been able to undertake, they are:

Patrick Walsh, Bishop of Waterford and Lismore

A solid suggestion for ‘PW’ which has emerged is that of Patrick Walsh, Bishop of Waterford and Lismore from 1551 until his death in 1587.

A solid suggestion for ‘PW’ which has emerged is that of Patrick Walsh, Bishop of Waterford and Lismore from 1551 until his death in 1587.

Bishop Patrick Walsh was in a very interesting position. The surname ‘Walsh’ is an Irish form of the surname ‘Welsh’. Bishop Walsh’s family background is not yet clear, but he did study in England at Brasnose College, Oxford. Prior to the Reformation he would have definitely used a Catholic bishop’s seal. Although he was appointed as a bishop of the Church of England it seems Bishop Walsh played both sides. Besides his spiritual domination he and his family also seem to have had most of the commercial aspect of Waterford sewn up. (Indeed, when Sir Henry Sidney was appointed Lord Lieutenant to Ireland he was met with a procession in Waterford organised by Bishop Walsh.)

Now, if the Bishop was a closet Catholic he might have thought it discreet (and in his own best interests) not to use a seal reflecting the English Church; but at the same time – for the obvious son verse reason – it would not have been sensible to used a seal which reflected the Catholic Church either. Hence the suggestion that he was a candidate for using something in-between. Alternatively it is perfectly possible – given his business interests (for which he would needed to travel extensively on a route which took him along the South Wales coast to England) – that he used two seals, one for religious and one for secular purposes.

It is again unfortunate that Bishop Walsh’s dates are somewhat later than the National Museum’s estimate of the age of the Druidstone Ring.

Philip Watkin

This is a name thrown up by ‘Maldwyn’, the online computer index maintained by The National Library of Wales, Aberystwyth, when we searched for bards with the initials of ‘P’ and ‘W’.

As far as we can see the index is completely in the Welsh language (so its use might be a bit tricky for non-Welsh speakers!).

Early days yet on our research of Mr Watkin.

Philip Williams, the Chief Secretary for Ireland

Quite early on, a name emerged which remains one of our stronger prospects – one Philip Williams, the Chief Secretary for Ireland.

The way it worked at the time was that the Queen (Elizabeth I) appointed a Lord Lieutenant to govern Ireland for her and the Lord Lieutenant appointed a Chief Secretary to do whatever needed to be done. Of course the Chief Secretary had sufficient power to also do what he, the Chief Secretary, wanted done.

Any particular Chief Secretary was very much linked to the relevant Lord Lieutenant; driven by the Lord Lieutenant’s power or lack of it they rose and fell together. It was most unusual (and require a high level of resourcefulness) for a Chief Secretary to serve under more than one Lord Lieutenant; this Chief Secretary, Philip Williams, between 1571 and 1597 served under three(!) – Sir William Fitzwilliam (in two different periods), Sir John Perrot and Lord Burghley. To have manoeuvred himself into alignment with three different lord lieutenants in a 25-year period (it’s hard to understand how he could have aligned himself with Sir William, then another Lord Lieutenant, then back to Sir William again!) must have taken some doing. But he did it!

But how come the ring was lost in south Wales?

All three of these lord lieutenants would have levied their armies in Ireland from, particularly, nearby Wales so there would be every reason for Philip Williams to visit the various land-owners around Wales (and the bordering areas of England) to ensure that the land-owners levy commitments were being met. The Druidstone Ring was found on what would have been a direct route along the few miles between Tredegar House (the seat of Lord Tredegar, a massive south Walian land-owner) and Druidstone House – presumably at that time a grand house nearby on the Tredegar estate, ideal for the accommodation of important visitors. Such as Mr Williams.

With this suggestion in mind, looking again at the imagery on the bezel of the Druidstone Ring it is easy to see how the flower and leaves, lightly dismissed in the Museum’s report as “floral sprigs” (of decoration), are perhaps not by accident positioned over and surrounding the harp; they may actually represent the English rose – thus creating a visual representation of England’s domination over Ireland. The five-petalled flowers on the shoulders of the ring – also mentioned in the Museum’s report – may now appear to be even more recognisable as representations of the Tudor rose.

Should this suggestion become proven, and that the Druidstone Ring was a tool of government, it is difficult to grasp the enormity of this find’s importance, particularly as it relates to the history of Britain’s relationship with Ireland, and also in terms of Britain’s relationship to the rest of the world. Now that would be a back-story!

Of course there will be documents written by Philip Williams, bearing his seal, stored in various places. (There is apparently at least one letter written by him to Queen Elizabeth I.) The briefest of visual comparisons of the seal used on those documents against the seal which we’ve found may be conclusively informative.

It has been suggested that the Chief Secretary would have used the Lord Lieutenant’s seal, rather than one of his own. We have seen a letter written by Philip Williams to Lord Cecil bearing Philip Williams’ own seal as the Chief Secretary. It is frustrating that the seal on the ‘Cecil’ letter does not match the ‘found’ seal. But of course, they could easily not match – he’d lost his first seal (we’ve found it!) and was using a second. Equally, given that theft was rife at the time in Wales, he may have carried with him his ‘reserve’ seal.

We are hoping that more examples of letters bearing Philip Williams seal will come to light.

In relation to his position as Chief Secretary of Ireland it would appear that Philip Williams was recommended to Sir John Perrot by Herbert, Earl of Pembroke (for whom Philip Williams and his brother John were servants). The Raglan Ring is claimed to have been the property of Lord Herbert. The style of engraving of The Druidstone Ring and the Raglan Ring are so similar that they could be the product of the same hand. Intriguing…

Philip Williams, deputy steward of Wentloog

Another in our growing band of Philip Williamses.

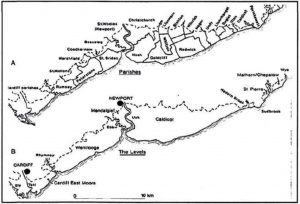

This Philip Williams was the deputy steward of Wentloog, a large area of countryside (see the map alongside which shows ‘Wentlooge’ stretching almost from Cardiff to Newport, a distance of approaching 12 miles) which extended to within a few miles of the find site of The Druidstone Ring. Unfortunately he was undertaking his duties there in the seventeenth century, somewhat later than the estimated date range of the ring, so it seems improbable that he’s our man.

This Philip Williams was the deputy steward of Wentloog, a large area of countryside (see the map alongside which shows ‘Wentlooge’ stretching almost from Cardiff to Newport, a distance of approaching 12 miles) which extended to within a few miles of the find site of The Druidstone Ring. Unfortunately he was undertaking his duties there in the seventeenth century, somewhat later than the estimated date range of the ring, so it seems improbable that he’s our man.

Philip Williams, Glyn y Esgair

Revealed by ‘Maldwyn’, the online index maintained by the University of Wales, Aberystwyth, This is one of several ‘Philip Williams’s – although the Welsh-language suffix to his name (customarily used in Wales to identify a person by his location) immediately differentiates him from the others.

Philip Williams of St Brides

We’re in the early stages of researching this Philip Williams.

We know he came from ‘St Brides’ but we don’t yet know which St Brides; there are more than one. But one is just a few miles from the site of the find of The Druidstone Ring.

We’ve come across him in The National Archives, in documents relating to ‘The Queen v. Philip Williams’. It seems the prosecution was: ‘Whether Philip Williams of the parish of St Brides has kept and maintained one able and sufficient gelding for a light horseman, with sufficient armour and weapons for the same, during the time his wife has worn a silk gown’.

Philip Williams, vicar of Newport

One of a growing number of Philip Williamses!

We know that this Philip Williams was a vicar in Newport, Gwent, just six or seven miles from the find site, in 1570 (a little late by the Museum’s dating of the ring) – and that’s about it!

A work in progress!

The Prince of Wales

Another very interesting, indeed exciting, suggestion is that the ‘PW’ initials could stand for ‘Princeps Walliæ’ – which of course translates into English as ‘The Prince of Wales’. In which case the ring could have been a possession of the young Prince Arthur.

Another very interesting, indeed exciting, suggestion is that the ‘PW’ initials could stand for ‘Princeps Walliæ’ – which of course translates into English as ‘The Prince of Wales’. In which case the ring could have been a possession of the young Prince Arthur.

Although only 15 years old when he died, Prince Arthur’s dates fit the National Museum of Wales’ estimate of the date of the Druidstone Ring and Prince Arthur would of course have been keen to show his support for the bardic tradition – not forgetting that harpers were among the highest of the many levels of bards… now that really is a back-story!

Wiliam Penllyn

A Welsh bardic harper of great repute. Everything fits (although perhaps his dates are a little late; he is known to have been alive between 1550 and 1570) – except his initials are the wrong way around. But they’re the right way around on the ring seal!

Could be…